California lawmakers enacted the nation’s strongest online privacy law in 2018 with the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), and voters strengthened that law’s protections at the ballot in 2020 with the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA). In many areas, the law gives consumers greater protections than the federal proposal currently moving through the House, the American Data Protection and Privacy Act (ADPPA).

Federal preemption in ADPPA would override California’s protections: exempting companies that provide data to government agencies from consumers’ privacy choices, leaving the law vulnerable to weakening by industry lobbyists, and swiftly canceling years of progress in California that has even spurred some large companies to expand those rights to consumers nationally.

It will also handicap the fight for reproductive rights.

That was the conclusion of the California Privacy Protection Agency, charged with enforcing our state law, in this letter opposing preemption sent to House Speaker Pelosi this week.

“The legislation should take head on the new world women are living in since June 24th the date of the disastrous Dobbs decision, which stripped the rights of women in our nation and potentially criminalized routine health care procedures,” said Eshoo in a statement.

“The bill before us has a major loophole that could allow law enforcement to access private data to go after women. For example, under this bill, a sinister prosecutor in a state that criminalizes abortion could use against women their intimate data from search histories or from reproductive health apps. That loophole must be addressed.”

Here are some key takeaways:

- California law protects against government surveillance. Governments and law enforcement agencies are using data brokers to avoid obtaining warrants for location and other information about Americans. California’s law applies to companies who contract with the government, allowing people to opt-out of data collection and stop their sensitive information from getting into the hands of the government. A major loophole in the ADPPA allows companies who contract with a local, state or federal government for data collection to avoid compliance with the law. That means unfettered access by governments to mass data collection by tech companies like Google as long as they have a contract.

- California’s law cannot be weakened – except by Congress. CPRA sets in stone a guaranteed minimum for privacy protections and cannot be weakened by the legislature without the direct consent of California voters. That means privacy in California has nowhere to go but up – unless Congress decides to preempt the law. ADPPA would replace California’s floor with a federal ceiling that stops states from enacting stronger protections. No matter how strong a federal law is, industry lobbyists will seek to weaken or even eliminate it with future legislation.

- Californians who are protected now would face a 2+ year delay. CCPA is already in effect, and 2020 amendments making the bill even more protective of sensitive data like race, sexual orientation and location will be implemented in less than 6 months. ADPPA overrides those rules and will put privacy on hold for at least two years as the Federal Trade Commission writes regulations.

- Preemption is a false choice. State and federal laws do not have to be binary. Strong federal privacy laws already co-exist with stronger state privacy laws. Many other federal laws, like the Clean Air Act, set a federal floor, not ceiling.

- For example: The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLB) and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) both established national policy “floors” and let states enact more privacy-protective legislation. Thanks to GLB’s policy floor, not ceiling, the CPRA built on it to give Californians stronger financial privacy protections. For banks that could mean, for example, any personal information collected and inferences made about a consumer as they consider a bank but before they sign up for financial services.

- Audits and enforcement. The California Privacy Protection Agency can audit companies’ compliance with the law; ADPPA would eliminate these audits. While amendments to ADPPA nominally allow California to enforce the law, the Agency cites “significant uncertainties” in its ability to do so. State enforcement matters because, while the FTC receives no new enforcement funding, the California Agency has a guaranteed $10 million annual budget.

- More protection against coercive pricing. California’s law has stronger protections when a company imposes differential pricing on consumers who exercise their privacy rights. It prohibits such charges from being “unjust, unreasonable, coercive or usurious” and requires companies to prove a different price for those who choose privacy is “reasonably related to the value provided to the business by the consumer’s data.” ADDPA would override these provisions.

- Direct opt-out of discriminatory profiling and automated decision-making. California’s law creates a right to opt-out of profiling and automated decision-making, allowing consumers to prevent discrimination in access to jobs, housing, loans, etc. that occurs when biased algorithms go to work and ignore civil rights. This broad opt-out from automated decision-making is in some ways more protective than the ADPPA’s bar on racial discrimination, because the ADPPA relies on companies to decide if their algorithms are biased. California’s law will allow consumers to simply say, “don’t profile me at all.”

- Broader right to delete data. California allows consumers to view and delete all of the data a company has collected about them since the law was enacted. Data deletion is limited to a two-year look-back in the ADPPA.

Don’t get us wrong: Everyone in America deserves strong privacy protections. We especially like the piece of ADPPA’s bar on discrimination that prohibits “disparate impacts” not just intentional bias when determining if a company’s practices – and its algorithms’ results – are fair. That’s crucial to making discrimination laws work. But setting this up as one or the other is a false choice. American privacy laws have long created a national floor, above which nimble states can innovate to enact stronger protections as the need arises. ADPPA would be a ceiling.

There’s one reason the tech industry likes the dichotomy: They don’t want to comply with California’s more stringent protections. Once Congress locks in a law we may not see movement again on the issue for decades. That’s why it’s incumbent on this Congress to get it right.

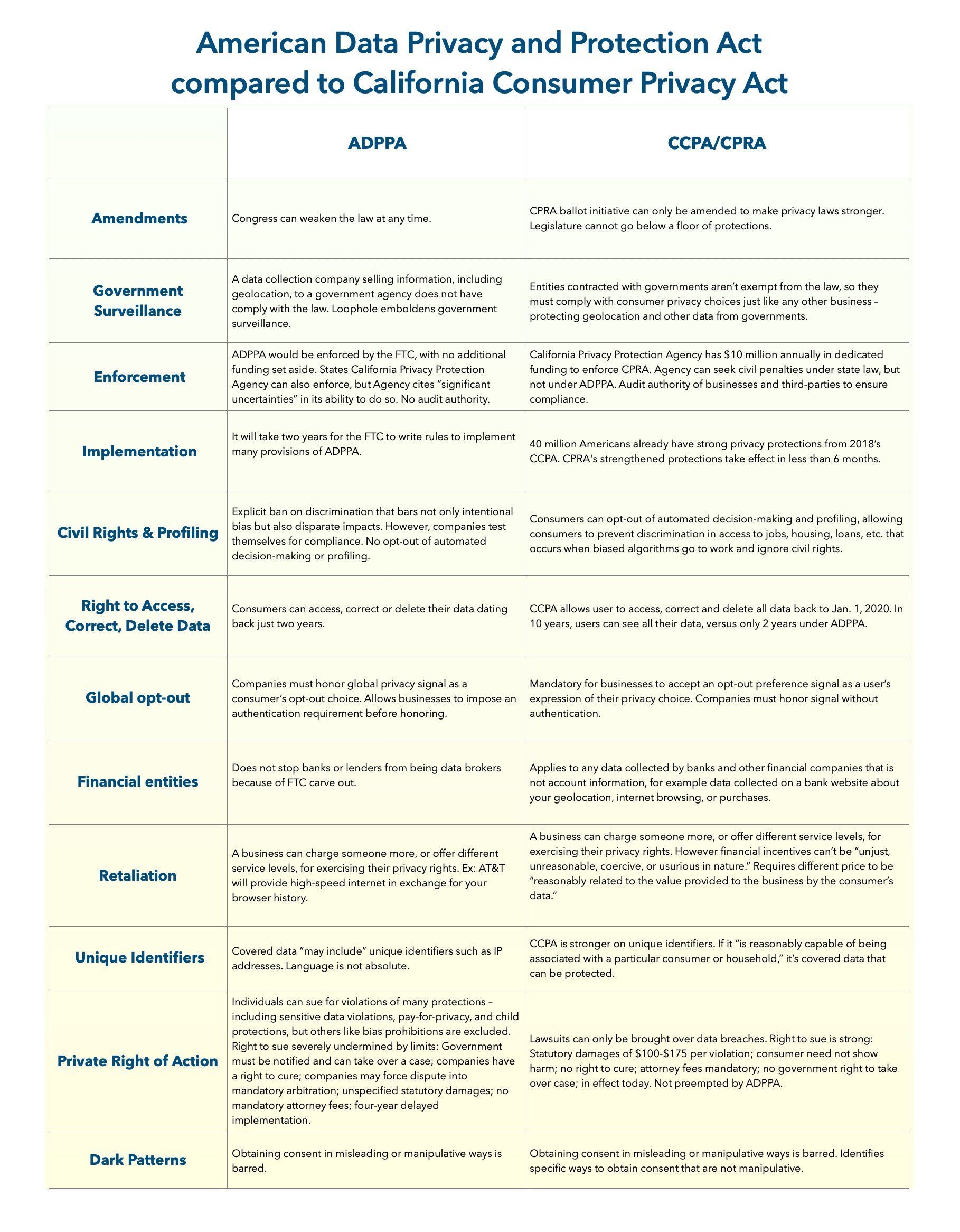

Interested in a comparison of the provisions of California’s law and the federal proposal? See the chart below, or download here as a pdf.