S., an otherwise healthy 51-year-old merchant marine, husband and father of three sons, went to the emergency room exhibiting clear signs of a pulmonary embolism — blockage of the pulmonary artery or one of its branches to the lung. The emergency room doctor suspected as much and ordered a CT scan to confirm.

Inexplicably, the results of the CT scan were misinterpreted as negative when they in fact were positive. The radiologist claimed that he told the ER physician that the results were positive even though the ER physician clearly wrote “negative” in the records. If the scan had been noted correctly, the life-saving anticoagulation treatment would have been started immediately and maintained until he was out of danger.

Instead, anticoagulants that were started shortly after admission to the hospital were stopped hours later and not restarted because of a communication breakdown between various doctors. While waiting for an additional test to be performed to look further for pulmonary embolism, a cardiologist who knew nothing about the suspected pulmonary embolism put S. on a treadmill to stress-test his heart. If the cardiologist had communicated with the primary care physician, he never would have performed a cardiac stress test because of the elevated risk it presented for a patient with suspected pulmonary embolism. The simple and essential communication never occurred and within one minute of starting the exercise treadmill test, S. dropped to his knees and could barely breathe.

Roughly twelve minutes later he was dead.

One of the expert witnesses in the case remarked that the events were akin to three fielders in a baseball game watching a pop-up fall between them — the fielders were doctors with a patient’s life at risk.

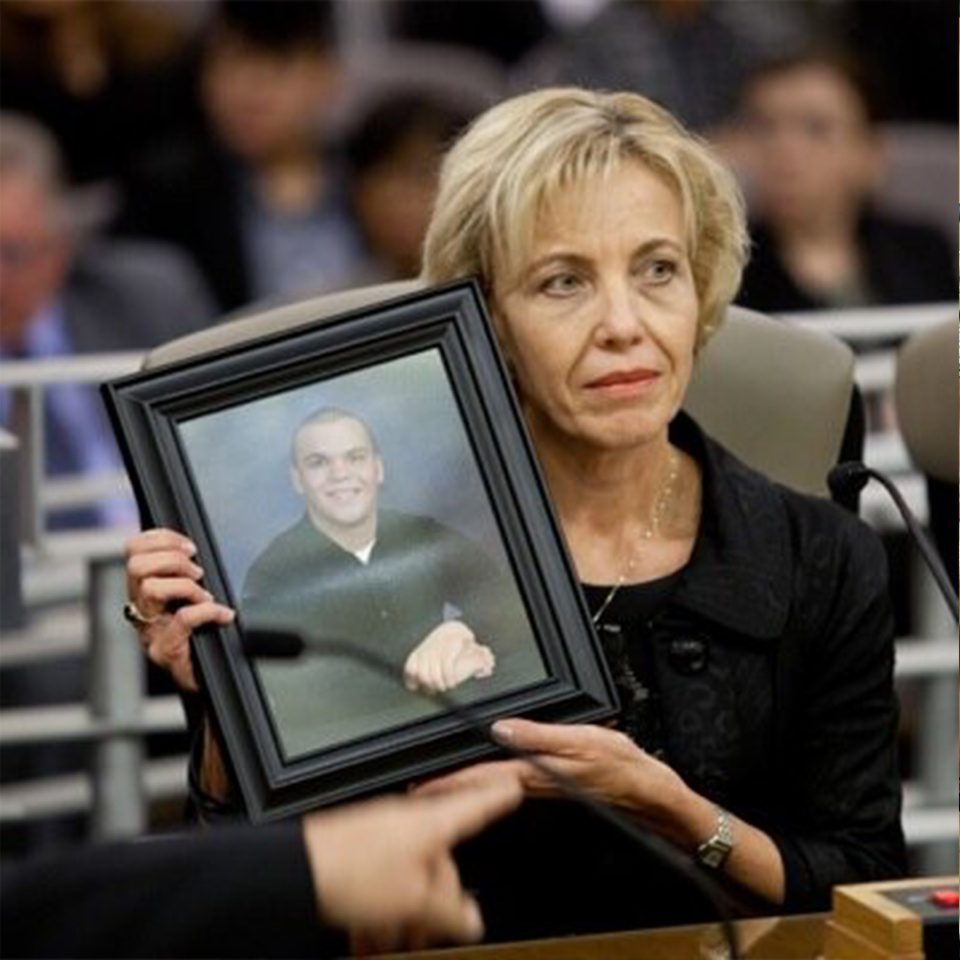

The horrific chain of events led to his death just short of his 26th wedding anniversary. S.’s condition was treatable, and he should have enjoyed a longer life with his wife, his sons, and his newborn grandchild.

When the case was resolved in 2013, the survivor damages for the emotional toll, and everything S.’s wife and three surviving sons had lost upon his, death were limited to $250,000. This inadequate maximum is the result of an enduring and outdated 1975 cap on compensation for medical negligence.