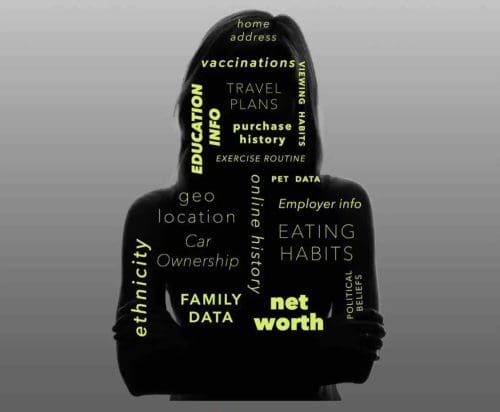

Recently, the Federal Trade Commission quietly released its initial study on surveillance pricing amid a flurry of missives during the final days of the Biden Administration. In short, the FTC found that retailers do use data such as scrolling habits, purchase history, and location in charging people different prices for the same product.

It’s not surprising, but it is still concerning. Last year, Consumer Watchdog outlined examples of surveillance pricing in a report titled “Surveillance Price Gouging.” Check it out. It’s likely everywhere, and it’s hard to spot. Amazon alone changes prices millions of times a day.

The variables used by companies include, “where the consumer is, who the consumer is, what the consumer is doing, and prior actions a consumer has taken, such as clicking on a specific button or element on webpage, watching a video, or adding a particular item to their cart or wish list,” said the FTC study.

“Price targeting tools can be used to generate pricing recommendations on different schedules, from monthly updates to minute-by-minute updates,” said the FTC study.

Among some of the hypotheticals the study gave included consumers profiled as new parents and charged higher prices as a result. An e-commerce platform could know that the parent prefers fast delivery of baby formula, infer the consumer is less sensitive to higher prices because they are in a rush, and charge them more. This could then result in said parent seeing higher prices for a number of baby-related products on the first page of their feeds, like baby thermometors, “based on their residential zip code and time of purchase.”

Or a person who visits the website for a financial institution using a U.S. IP address with their language default set as “Spanish” might be offered different credit cards. In another example, a price targeting tool could tailor its website so that visitors see only specific prices featured in the store based on consumer proximity to other competitors. In an example we pointed out, Staples.com charged people more for the same stapler if it knew a person had fewer options, such as being near a competitor.

Or a pharmacy could choose to exclude regular customers in a special promotion for over-the-counter medications or weight-loss supplements “because the pharmacy inferred that those customers are likely to buy those products anyway,” according to the study.

Even how long we take to respond, and how we engage with emails is tracked and incorporated into pricing.

The study examined documents it obtained from Mastercard, Accenture, PROS, Bloomreach, Revionics and McKinsey, who are hired by retailers to consult on pricing. These companies work with at least 250 clients that are not named, ranging from grocery stores to apparel retailers to travel, health, and financial service companies. The FTC determined that widespread adoption of surveillance pricing might completely change how consumers buy things and how companies do business. In our report, we cite how corporate consultants have been pushing for it. “Personalized pricing strategies, once considered a futuristic concept, have become a cornerstone of modern business strategy,” said the Cortado Group. McKinsey said, “Our experience shows that such transformations, when done well, can enhance pricing to generate two to seven percentage points of sustained margin improvement with initial benefits in as little as three to six months.”

The FTC study is only preliminary, and doesn’t state whether the pricing is illegal or not. More importantly now though is what happens next. The new FTC chairman, installed by Donald Trump, is Andrew Ferguson, a Big Law alumni who defended large companies from antitrust cases and opposed consumer gains such as the commission’s non-compete ban. He opposed releasing the pricing study, and one of the first things he did as chair was to shut down public comments for it. So it looks like this is the end of the FTC looking into surveillance pricing.

But the study said there is much more work to do. This means it is up to states like California to continue the work the FTC started, in the form of legislation, advocacy and legal action, as the study only presents a sliver of information the FTC hopes to acquire. As the study says, there is a lot we still don’t know about how surveillance pricing works.

“Data inference mechanisms can be varied, and the study documents did not fully outline or represent how some inferences were derived…These summaries are limited due to information that is still being gathered.”