By Michael Hiltzik, LOS ANGELES TIMES

Uber loves to define itself as a most public-spirited company.

“We’re reimagining how the world moves … to help make transportation more affordable, sustainable, and accessible for all (opens in new tab),” as the ride-sharing giant declares on its website.

In 2020, when it spent nearly $100 million to pass Proposition 22, which overturned a state law designating its drivers as employees, gaining them benefits such as a minimum wage and workers compensation coverage, it described the goal of the ballot measure as granting the drivers “the flexibility to decide when, where and how they work (opens in new tab).” Never mind that the initiative protected Uber’s business model, which involves sticking its “independent contractor” drivers with the cost of fuel, insurance and wear and tear on their vehicles. The initiative passed.

San Francisco-based Uber is now back in the ballot initiative game, this time with a proposal for a state constitutional amendment (opens in new tab) capping the fees of plaintiffs’ lawyers representing victims of auto accidents. The proposal, which is in its signature-gathering phase, is aimed at the November ballot.

The initiative text is replete with vituperative language attacking personal injury lawyers as a class. It labels them “self-dealing attorneys” and “billboard attorneys,” and accuses them of deliberately inflating their clients’ medical claims so they can grab a larger fee and engaging in unsavory and perhaps illegal sub-rosa arrangements with complaisant medical providers.

Its putative target is contingency fees, which are typically percentages of the payouts awarded by juries or through negotiations. These are common in personal injury cases, because the clients often don’t have the wherewithal to pay a lawyer’s retainer fee in advance.

The initiative would cap contingency fees at 25% of the award. “Automobile accident victims deserve to keep more of their own recovery,” the initiative says.

“Capping attorney fees, banning kickbacks, stopping inflated medical billing and putting in place whistleblower protections will protect auto-accident victims and have the additional benefit of reducing costs for consumers,” Nathan Click, a spokesman for the initiative campaign, told me by email. He labeled the initiative a “common-sense” reform.

(Just as an aside, whenever I see a legislative proposal described as a “common-sense reform,” I reach for the nearest vomit bag; the phrase almost always is applied to a measure larded with concealed drawbacks, as is this one.)

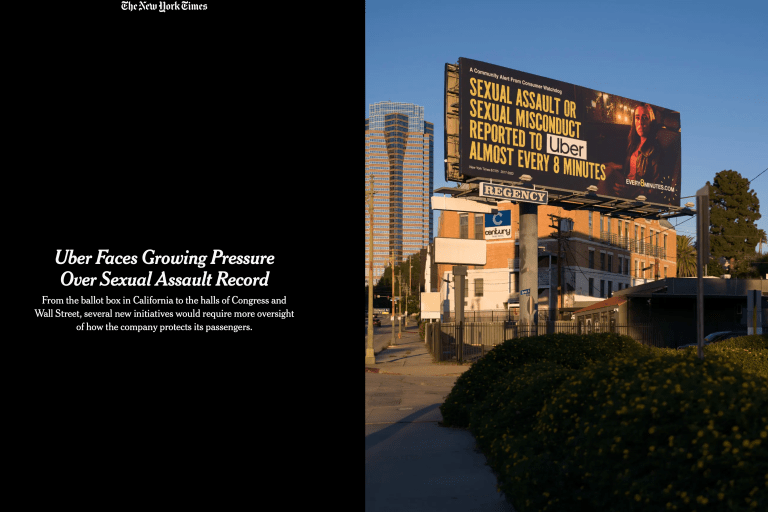

Superficially, this looks like it could be a win for accident victims. But it’s not really about them; it’s about Uber, which has been the target of lawsuits stemming from injuries its passengers suffer while traveling with its drivers.

Uber doesn’t say how many lawsuits it has faced from passengers, or the size of its financial exposure. But in its most recent annual report (opens in new tab), the company acknowledged it “may be subject to claims of significant liability based on traffic accidents, deaths, injuries, or other incidents that are caused by Drivers, consumers, or third parties while using our platform.”

Uber’s bete noire on this issue is Downtown LA Law Group of Los Angeles, which Uber sued (opens in new tab) in federal court, accusing the firm of “racketeering” and “fraud.” The firm moved to dismiss the suit, but briefing on that won’t be done until spring at the earliest.

I asked Click why Uber thought its accusations against Downtown LA Law Group are so egregious that they warrant rewriting the state constitution. He replied that the Downtown LA case is just “the tip of the spear.”

The law group has been the subject of an investigation by my colleague Rebecca Ellis, who has reported that that nine of the firm’s clients who sued over sex abuse in L.A. County facilities said recruiters paid them to file a lawsuit, including four who said they were told to fabricate claims. The L.A. County District Attorney’s Office is conducting a probe into the allegations. (The law firm denied the accusations.)

But nothing in Ellis’ reporting or what’s known about the county investigation validates Uber’s implicit argument that its behavior is generally characteristic of the plaintiffs’ bar.

The Uber initiative is the latest sally in a long war pitting plaintiffs and their lawyers against businesses, with legal fees as the battleground. In this war lawyers invariably are depicted as soulless and grasping ambulance-chasers unconcerned about their clients’ welfare, and businesses as, well, soulless, grasping and unconcerned about their customers. In the past the battle has been waged between lawyers and doctors, but with this initiative campaign nothing has changed other than the identity of the defendants.

Click pointed out that nothing in the proposed measure would prevent accident victims from suing Uber. But that’s hardly the point. Capping contingency fees makes many lawsuits uneconomical for attorneys, who must shoulder litigation costs such as expert testimony until a final judgment is achieved, and are left holding the bag if there is no recovery or the judgment doesn’t cover their costs. So this initiative, if passed, almost inevitably would reduce the tide of lawsuits filed against Uber.

Indeed, what gives this effort the stench of cynicism and hypocrisy is that we have plenty of experience about what happens when contingency fees are capped: Plaintiffs who have suffered grievous injury (or if they’ve died, their survivors) have trouble even getting through the courtroom door.

The lesson comes from California’s Medical Injury Compensation Reform Act of 1975. MICRA capped the noneconomic recoveries — think pain-and-suffering or reduced quality of life — for plaintiffs in medical malpractice cases at $250,000. It also capped plaintiffs’ attorney’s fees on a sliding scale, to as little as 21% on recoveries of six figures or more.

The idea was that the reduced attorney fees would make up for the reduced judgments, but according to a study by the Rand Corp. (opens in new tab), that didn’t happen. Plaintiffs’ net recoveries were still about 15% lower than they would have been without MICRA, Rand deduced. The result was “a sea change in the economics of the malpractice plaintiffs’ bar,” Rand found, with cases where the judgment cap would cut too deeply into attorney fees getting short shrift.

Those cases tended to be those with “the severest nonfatal injuries (brain damage, paralysis, or a variety of catastrophic losses)”; the median reduction in those patients’ recoveries was more than $1 million. After years of efforts the legislature finally amended MICRA in 2022, when the cap was raised to at least $350,000, with raises placing it at up to $1 million by 2032, followed by annual adjustments to accommodate inflation.

Uber’s proposal would have a larger blast zone than MICRA. Automobile-related injuries are more common than medical malpractice cases, but the range of injuries would seem comparable, up to and including death.

“This would affect every accident in the state,” says Jamie Court, the president and chairman of Consumer Watchdog, the California-based consumer advocacy organization. “Uber is trying to stop all cases, not just bad cases.”

It’s hard to reconcile Uber’s solicitude for accident victims with its most recent legislative victory in Sacramento. That was the passage of SB 371 (opens in new tab), a measure that cut Uber’s legally required insurance coverage when its drivers and passengers are injured in accidents caused by uninsured or underinsured motorists from $1 million per event to a mere $60,000 per person and $300,000 per incident.

In effect, as an Assembly analysis pointed out, the law shifts costs previously covered by premiums paid by Uber and its fellow ride-sharing firms to their drivers, who pay through their own insurance premiums — and even to passengers, if Uber’s insurance doesn’t cover their injuries.

Uber argued, with supreme nerve, that the $1-million policy requirement was what placed it among the “prime targets” of unscrupulous personal injury lawyers, because the prospect of a big judgment was what got the lawyers’ saliva flowing.

SB 371 sailed through both houses of the state legislature without a single votein opposition and was signed into law by Gov. Gavin Newsom in October. I asked Uber why, given the greased passage of a law it desperately desired, it didn’t take the same route to cutting contingency fees rather than an initiative campaign that will swallow up tens of millions of dollars. Click responded that the law specifically covered only the uninsured and underinsured motorist coverage that only the ride-sharing companies have to carry. The initiative, he said, “is much broader.”

If the Uber initiative reaches the ballot, spending by its supporters and opponents might well set records. Uber seeded the campaign with a $12-million contribution (opens in new tab) in October. But that’s probably just an amuse-bouche, launching a full-size meal.

The initiatives’ target, the personal injury bar, has responded in kind. They’ve proposed two counter-initiatives — one to increase the liability of ride-sharing companies (opens in new tab) for injuries to their passengers, and another giving Californians the constitutional right to contract with any attorney (opens in new tab) on any agreed-upon terms. Those initiatives are both in the signature-gathering phase.

Consumer Attorneys of California, the bar’s lobbying organization, already assembled a war chest approaching $50 million in contributions from lawyers and law firms.

Fasten your seat belts. Both sides are just getting started.