After nearly two years of negotiating and little progress, the international group trying to agree on a Do Not Track standard is convening its final official face-to-face meeting next week in Sunnyvale, Calif.

Although many people may not know that advertisers and other third parties operating on Web sites install cookies, which are small bits of code that track users’ browsing history, a small subset of consumers have already activated the Do Not Track mechanisms on their devices. These don’t-track-me browser settings send out signals telling third parties that a user does not want to have his or her online activities tracked.

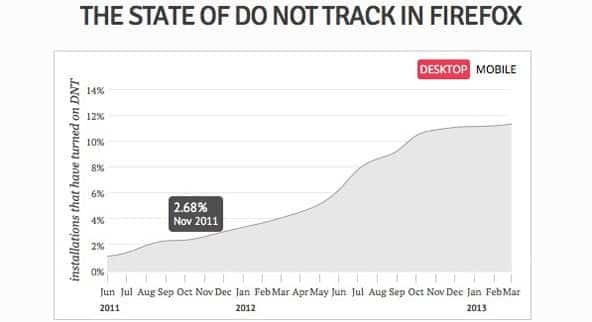

As of March, for instance, 11.4 percent of the estimated 450 million people worldwide who use the Firefox desktop browser had activated the Do Not Track setting, according to a new report Friday from Mozilla.

Advertisers say they need to collect tracking data in order to show relevant ads to consumers. Without behavior-based ads to support free content and services, they argue, certain sites would have to shut down or start charging for access. Privacy advocates, for their part, argue that consumers have a right to choose not to be tracked by companies they don’t do business with. If the price consumers have to pay is more generic ads that are not tailored to them, they say, so be it.

“Most people don’t realize the extent to which this brazen online tracking is done, but when the practice is described, they want to be able to control it,” John M. Simpson, the privacy project director at Consumer Watchdog, wrote in a blog post earlier this week. “Why should a company I know nothing about, have no say over and no relationship with be able to collect information about my online activity?”

If the tracking protection group of the World Wide Web Consortium or W3C, the international standards body that has been trying to create a consensus for the privacy mechanisms, fails to come to an agreement, however, these signals could end up having no more significance than white noise.

In an effort to get participants to cut a deal, Peter P. Swire, a law professor at Ohio State who is the co-chair of the W3C tracking group, circulated a draft proposal earlier this week.

The proposal said third parties would agree to not collect tracking data on any browser where a consumer had actively turned on the privacy signal. But companies would still collect data for certain permitted uses.

Stuart P. Ingis, a lawyer representing the Digital Advertising Alliance, an industry group that offers consumers an ad choices program, said that, from his point of view, two major issues remained to be resolved: ensuring consumers themselves choose to activate the privacy option and determining the kind of data that third parties could continue to collect and use even after a consumer activated the privacy signal.

“If progress can be made, that could clear a path to a conclusion,” Mr. Ingis said.

Some consumer advocates and technologists see additional sticking points, however, objecting to a number of prescriptive clauses in the proposal that could limit the way browsers present Do Not Track preferences to their users. A few advocates even suggested that the two sides are so far apart that the negotiations might as well be terminated.

The proposal, for example, says any Do Not Track button should be off by default, rather than set to a neutral position that would allow a user to turn the signal on or off. It also says that any Do Not Track mechanism should be located only in the browser setting – not through a browser “installation process or any other similar mechanism.” That would come as a challenge to browsers like Internet Explorer 10, in which Do Not Track is one of the choices offered during installation.

Jeffrey Chester, the executive director of the Center for Digital Democracy, a privacy group, said the proposal seemed intended to limit the number of consumers who would turn on a don’t-track-me signal.

“The industry wants to make it hard for people to turn on Do Not Track and that should be a deal breaker,” Mr. Chester said. “It should be prominent, simple and effective. Right now, the proposal fails to deliver that.”

But Mr. Ingis of the Digital Advertising Alliance argued the mechanism wasn’t important enough to consumers to be presented during browser installation.

“By putting it in a browser setting, you create a little bit of friction so that you make it simple enough for people who want to find it,” he said. “But you don’t treat it as if it’s a matter of national security, because it’s not.”

These stances seem so far apart that some now foresee a permanent stalemate. Jonathan Mayer, a graduate student in computer science and law at Stanford University who has been participating in the talks, says it’s time for the group to have a conversation about how to shut down the negotiations altogether.

“I think it’s right to think about shutting down the process and saying we just can’t agree,” Mr. Mayer said. “We gave it the old college try. But sometimes you can’t reach a negotiated deal.”